Date: November 25th, 2025

Note – If I’ve left your favorite place off the list please drop me an email I’ll include it.

Canmore has really taken off in the last 15 years–better food, coffee, more choices, and of course rapidly rising prices–most everything has gone up about 50 percent in the last few years.

Coffee (is food too):

Eclipse has multiple locations, and they’re about the best in town. Very light on food items but good. An “Analog Coffee” is supposedly opening “soon.” Communitea also.

JK bakery has the least expensive and pretty good breakfast sandwich in town, two locations. Also good for soup and sandwich lunches, baked goods, reasonable prices, etc. Old school canmore that somehow is surviving.

Communitea: Canmore is too expensive for hippies, but Communitea is where they would go if they could afford. Really nice owners, best cappuccino in town, organic foods, a really good addition to Canmore Downtown. A good “rest day” place to chill out. Healthy organic bowls and such, lots of moms with strollers and people using the place as an alternate office (free wifi). They also book some surprisngly good acts in the evenings too.

Summit Cafe: Good breakfast food, crowds of active people scheming activities every morning, nice atmosphere, good morning sun on the deck. Canmore’s best breakfast place. Lunch a little variable but the chicken club is solid. No dinner.

Bagel Bakery (two locations): Good prices, good food, weak coffee, open late on main street (busy during the day), occasional live music in the evening. Their breakfast bagels are great morning food.

Beamers (two locations): OK coffee and simple food, open very early in the morning, fast service (a rarity in Canmore) zero attitude. One locaiton on the 1A, one right across from the post office (Rusticana on main street). Common meeting place for guides and clients.

Harvest, beside Switching Gear: A bit limited menu but good food, the “Stuffed French Toast” seems like an odd idea but is awesome. Popular with locals, unknown to tourists in general.

JK bakery again.

Bella Crusta: Best deal in Canmore for lunch, good and reasonable bread-style pizza (toppings on big pieces of round bread, excellent) lunch stuff across from the huge Stonewaters furniture store just off main street. I sometimes take some of his “heat and bake” pizzas, cook ’em up, and take them climbing, excellent lunch. The owner is a Canmore classic and good guy.

Valbella’s Deli: High-quality and great tasting food, surprisingly reasonable given what you get. In the industrial park near the police station on Elk Run. The lunch special here is a real meal; usually something like a big plate of curried chicken and rice, or some Euro thing, but definitely the best “real food” lunch buy in town. They also make their own meats, great place to get trip or BBQ food.

Ramen Arashi. My favourite. Great food, people, and as spicy as you wanna go!

Red Rocks Pizza: A really good value, nice owners, also have good beer on tap, local favourite for when you just want a decent Canadian style pizza without feeling gouged or dealing with a scene. Limited seating in winter, but a big deck in summer. If you get one pizza the second one is a deal usually, so you can get two large pizzas for $45 and eat lunch for the week.

Georgetown Inn: Good climbing memorabilia, decent food, Brit-inspired pub. Cosy, chill, good for a mellow dinner and a few beers. Nice place to stay too.

Spice Hut: An informal, post-climbing reliable go-to, always popular with my friends. Order it “Double Extra Hot!”

Grizzly Paw Brewery: Good solid middle of the road pub food and beer. Not greasy, not gastro-pub, just good pizza, burgers, salads and a good staff.

Iron Goat: Up in Cougar Creek (the sunny side of the valley). A really good place to go for a pint in the bar, or a solid meal on the restaurant side of things. This restaurant was started by a friend of mine–he reportedly invested a lot of money because he was sick of not having anyplace in town to go to get a good beer and good food in the evenings. I think he succeeded in solving both his problems.

Wild Orchid: One of the best places in Canmore. It’s a sort of pan-Asian vibe with really creative food, best sushi in town (limited selection, but good), and a great evening deck. The bill for three people with some wine is really reasonable given the quality of the food.

Sage Bistro: On the 1A in the old log cabin. Creative but “real” food at good prices, good wine selection at reasonable prices. All in all a surprisingly good place to eat given how it looks, with that rarest of rare occurences in Canmore, really good service.

Crazy Weed: A little expensive but worth it. Reliably good food, solid wine list, this is where you go when you want to get your big city on but mountain style.

“Special” Food & Needs

Late Night and Early: Tim Horton’s is open when you need it to be, Beamers is open at 6:00.

Vegan: Go back to Squamish, this is Alberta y’all!

Canmore is now expensive to stay in. Really expensive. You can get better deals in October, November, April and May, but the rest of the year is just going to cost you.

Alpine Club Hostel: Hostel-style, but clean, cheap, good place to find partners. Just outside town (you can walk if you’re a European, Americans will need a truck).

Canmore Hostel Great location, reasonable prices generally, young scene.

Georgetown Inn: Non-chain, nice kinda frilly rooms. Close to the hospital if all goes bad, good food too.

Malcolm Hotel: Arguably the nicest in town, good food and people.

Where NOT to stay: No really bad places in town, with the possible exception of our futon. Lots of chain hotels and good basic places.

Tavern 1883: Replaced Zona’s, good scene for adults, decent cocktails.

Sheepdog Brewing: Good local scene off the beaten path in the industrial park. Good beer, basic snacks but you can bring your own.

Georgetown: You may risk falling asleep in your beer, but it’s good beer and a nice scene.

The Drake, Rose and Crown: Unpretentious bars with food. Right across the street from each other. Beer, food.

The Mine Shaft: In Spring Creek, and attached to the senior lodge there somehow by sliding doors. Good prices, fun people, don’t laugh until you’ve tried it, one of my secret favourites.

Banff: is where you’ll need to go for serious night life, Canmore just doesn’t have it.

Climbing Gear: Vertical Addiction, near Safeway, is our true small specialty store with just the right quantity of maps, shoes, ropes and other outdoor hardware. The owner, Benoit, has worked really hard to make this place a success, and it’s great to have it here in town. Prices are usually competitive with Calgary too, a rarity in Canmore.

Valhalla Pure has a larger selection of clothing, travel and camping stuff/pots and pans, and also sells a small selection of hardware. Nice people too.

Climbing Gym, showers, weights, stretching, library, kid care. It’s all under one roof: Elevation Place is our Taj Mahal of a town rec centre, and it’s a great addition. The climbing gym is well run and often staffed by injured mountain guides and other over-qualified folks, but a good scene. The routes are best described as bouldering on a rope, and graded with the lowest grade the setter can say with a straight face so check your ego and elbow tendons before arriving or drive to Calgary for routes with footholds. Good bouldering.

The Canmore Climbing Gym is our small but good bouldering gym, solid local scene. Everything you need to climb 5.15. Avoid the after-work hours, it gets really busy, but chill the rest of the time.

Gear Up: rents most ice climbing and mountaineering gear (boots, ice axes, crampons, etc) if you need some in a hurry, nice to have this service in a local shop. The staff there is also knowledgable about touring gear (re-does skins, mounts bindings, etc), good people.

Grocery Stores: Sav-On and Safeway are both monolithic big city style stores; Sav On does have the better selection. Nutters (in the strip mall across from the Drake and the Rose and Crown) has a lot of organic produce in a small space (well, it’s about 1/500th the size of the average Whole Foods but at twice the price). Valbella’s has good meats, bread.

Rusticana is a downtown convenience store that’s open early and late, and has some “real” groceries at a decent price. Good selection of Red Bull too :).

Fergies is up near Cougar Creek Canyon, and beside the Summit Cafe so convenient to have breakfast and pick up last-minute stuff before recreating.. Great Quebecois owner too.

Cellar Door: Most of our small, independent liquor stores have been bought up by big chains. This sucked, but the Cellar Door is really good. Strong on great value wine, expensive craft beers.

Buy Cheap Outdoor Gear: Switching Gear often has great deals due to local sponsored athletes surreptitiously selling surplus sponsor swag (seriously).

Laundry: On main street beside the Grizzly Paw.

We have three solid shops in town. The Bicycle Cafe is good and the “cool” shop in town (and has arguably the best coffee, worth visiting for that alone). Rebound has gone increasingly Roadie, good staff (the owner fixed up a 20-year old burley with parts he had lying around, pretty cool.) Excellent mechanics. Outside is a no-nonsense working class shop, solid mechanics and bike selection. It’s a bit like going to church, find where you feel at home.

Recommended Guides:

Me. But more on this list soon!

Posted in: Blog

Tags: Canmore, Climbing, Food, Gadd, Gear, Hotels, Restaurants

Date: November 25th, 2025

We welcome a lot of visiting and new local ice and winter alpine climbers to the Canadian Rockies every winter for a simple reason: It’s the best ice climbing in the world on average. We have a unique combination of consistent, highly varied climbs from bolted mixed dragging to alpine romps to super sketchy mixed routes, and access ranging from roadside to multi-day death marches. Be careful what you ask for because you’ll probably get it and then some in the Canadian Rockies. Ice climbing here can be sunny casual on some days, but on other days, well, shit gets very real, very fast. We generally have a lot of avalanche hazard on the vast majority of our climbs, solid professional but slower rescue service than the Alps, short days, bad roads, wind, cold, dark, etc. Figuring out what to climb in what conditions can be tricky.

Start here for a big picture look at how our season generally runs. We can generally climb water ice about ten months a year, with “decent” conditions generally running from mid-October until most people are sick of ice, around April 1, but there’s usually something left to climb into early June.

Quick Workflow Overview:

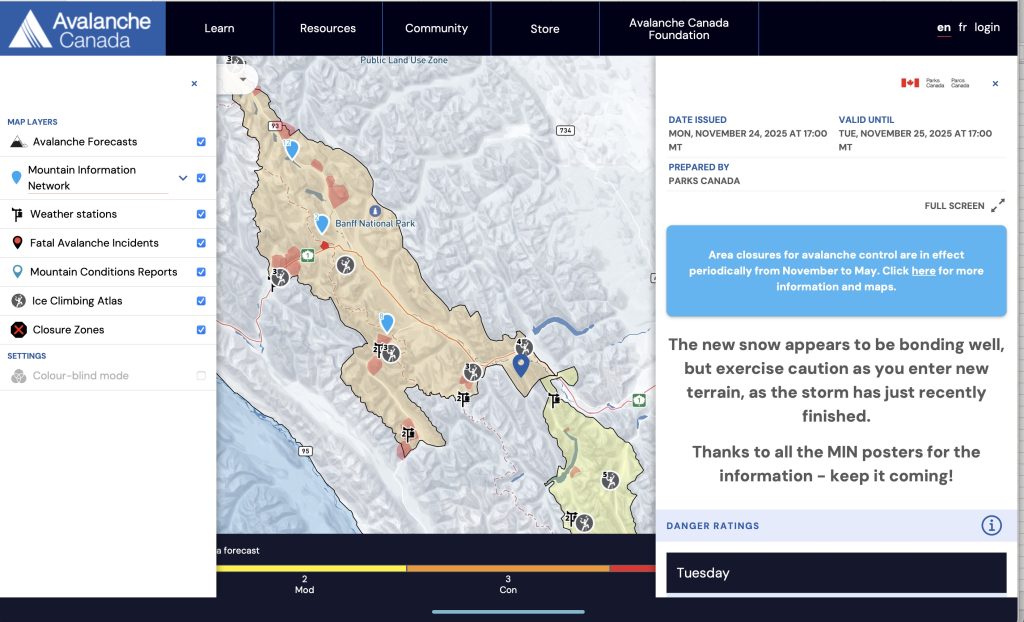

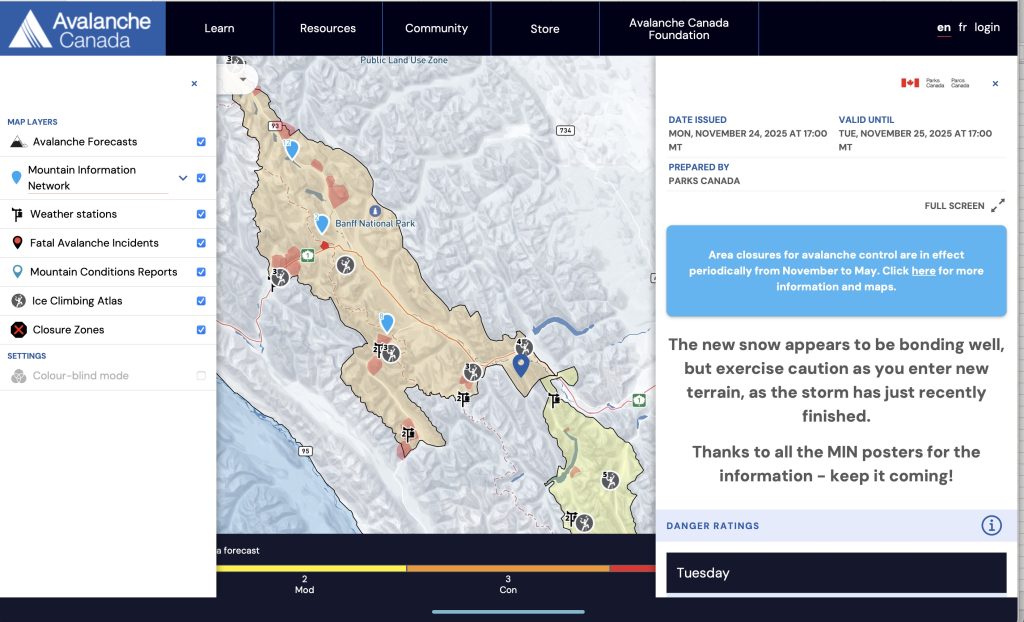

1. Start on avalanche.ca for avalanche danger forecasts. That hazard level and the terrain determines where to climb, not what I want to climb. Also look at it for winds, the Ice Atlas, new snow, general mountain forecast, MIN reports, etc. etc, it’s just great.

2. Look at the public weather forecasts for Canmore, Lake Louise, Jasper, and maybe Radium.

3. Look at social media, see below. With the MIN this should give a pretty good idea of what’s going on.

4. Research. Use the Ice and Mixed App for location info etc. Short list a few climbs.

5. Pull a Spot WX specific forecast for your potential climb. If you don’t use this already learn it, it’s great. Look at the winds at various levels.

6. Check road conditions.

7. If climbing in terrain that can slide bring avalanche gear at least to the base.

8. Bring satellite coms. Some phones work some of the time sometimes. Bring a dedicated sat com device.

9. Ice Climber’s code. Yes.

10. Send and Survive.

Detailed Workflow Overview:

Step 1: Avalanche Canada Map

Avalanches have killed far more winter climbers in the Rockies than anything else. On average, a climber dies here in a slide every year. This site is the critical overview for many snow-related resources, not just what the avalanche hazard is. Right away you can see the colours representing from “Low” to “Extreme.” Most places in Western North America have similar sites. The areas in these forecasts are generally in the range of 100km north-south, so they are very broad generalizations, but still a critical place to start for many reasons. I like to click on each forecast area that I might climb in, from Jasper to Kananaskis country or so, and then scroll down to the “specific problems” sections and all the relevant information there. The detail matters, and will help understand how the forecaster was thinking who wrote it.

Rule of Thumb (ROT) 1: For ice climbers, add at least one “level” to the danger rating scale. The CMOH (conceptual model of avalanche hazard) that drives the ratings is built around the size and probability of slides, and the consequences of the same–and much of the data and perspective in the CMOH is based on skiers and cars, not ice climbers, and on the “good” snowpacks skiers tend to seek, not the north-facing facet farms most ice climbs are in. A size 1 is by definition survivable for a skier, but for ice climbers even a small 1 is very much enough to ruin our day by knocking us off on lead or sending us over a cliff edge if walking between steps. A size two that would be relatively easily avoided by a skier on a planar slope is very different than a size 2 filling up a ten-foot wide ice gully 15 feet deep…. Most ice climbs are in nightmare terrain traps, and climbers have been killed in slides that wouldn’t likely ruffle a skier’s feathers much. We’re often also in gully features below big, multi-aspect terrain, so, unlike skiers, anything that slides on any aspect above us will end up hitting us. And we’re there for hours, tied in place. And we can’t adapt fast to changing conditions by pointing the skis downhill and getting out in minutes, or changing aspect. So, I add a level to the danger rating, and have found that to be a more accurate representation of the hazard.

Rule of Thumb (ROT) 2: If the “Danger Rating” is above “moderate” at any altitude I’m in or exposed to I’m generally just avoiding avalanche terrain greater than 2 (challenging) on the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES). There are enough routes to climb that are a 1 or 2 on the ATES scale (see list in link here from Parks Canada here) in the Canadian Rockies that you an almost always go climbing. Even with “moderate low low” climbers have died here. If you’ve spent a lot of time in the snowpack and terrain here then you will probably be able to make your own more nuanced judgements, but to me “Mod Low Low” means “Considerable” in the Alpine, Mod at treeline, and Mod below treeline. I’ve been there when the day goes bad, and you do not want that experience.

Step 2: Mountain Information Network (MIN) Reports, Ice Atlas,

The blue icons are field reports from climbers and skiers like you, and they often include ice and snow conditions, relevant avalanche observations from skiers, trends, etc. etc. It’s just great stuff, and I go through all the new ones every day. Info on snow, route conditions, obs from the day, this is just great stuff. There is also a “mountain weather” forecast aimed at notable weather events that will effect mountain sports types. You can turn the different “MIN” reports to just ice climbers or skiers, I generally look at all of them. A red dot in the middle of the blue indicates an incident, black a fatality. This is awesome. On the same Avalanche Canada Map, note that there are little “ice climber” icons. These are in most of the common areas, and link to “Ice Atlas” overview of the climbs with ATES ratings, slide paths, useful historical observations, etc. This is excellent into.

The blue icons are field reports from climbers and skiers like you, and they often include ice and snow conditions, relevant avalanche observations from skiers, trends, etc. etc. It’s just great stuff, and I go through all the new ones every day. Info on snow, route conditions, obs from the day, this is just great stuff. There is also a “mountain weather” forecast aimed at notable weather events that will effect mountain sports types. You can turn the different “MIN” reports to just ice climbers or skiers, I generally look at all of them. A red dot in the middle of the blue indicates an incident, black a fatality. This is awesome. On the same Avalanche Canada Map, note that there are little “ice climber” icons. These are in most of the common areas, and link to “Ice Atlas” overview of the climbs with ATES ratings, slide paths, useful historical observations, etc. This is excellent into.

Step 3: Social media cruise

Particularly Rockies Ice and Mixed Conditions, the biggest Rockies conditions page, and Rockies Ice Discussions. Both of these groups have a high information to drama ratio compared to the other offerings, and a lot of solid info. Photos, etc. I’m looking both at what’s in and not in, and what aspect/elevation/location those reports are from. For example, if the Sorcerer (high, north facing, Ghost) is in then probably Hydrophobia (same) is too even if there’s no report, same with the Joker. If Cascade (lower, south facing, high flow rate) is in then probably routes like Takkakaw are too (higher so colder but south facing and high flow).

Step 4: General Weather.

I usually start with the Environment Canada general public forecast for Jasper, Lake Louise, Banff, Radium and Bow Valley Provincial Park, or just a few of those. Is anything big coming in? From which direction? Is it going to “upslope,” meaning snow like crazy on the eastern side of the Rockies (Bow Valley Provincial Park) or is it big and wet coming in from the west (Radium etc)?

Also note the Sunrise and Sunset times, found at the bottom of these pages. These matter here, especially Nov-Feb. It’s dark a lot, and you need to plan accordingly.

ROT 3: If the forecast calls for more than 5cms in the 24 hours before or during when I’m climbing I’m going to an ATES 2 or maybe 3 zone only. More than 10cms I’ll wait 24 hours after it winds before heading out into avalanche terrain.

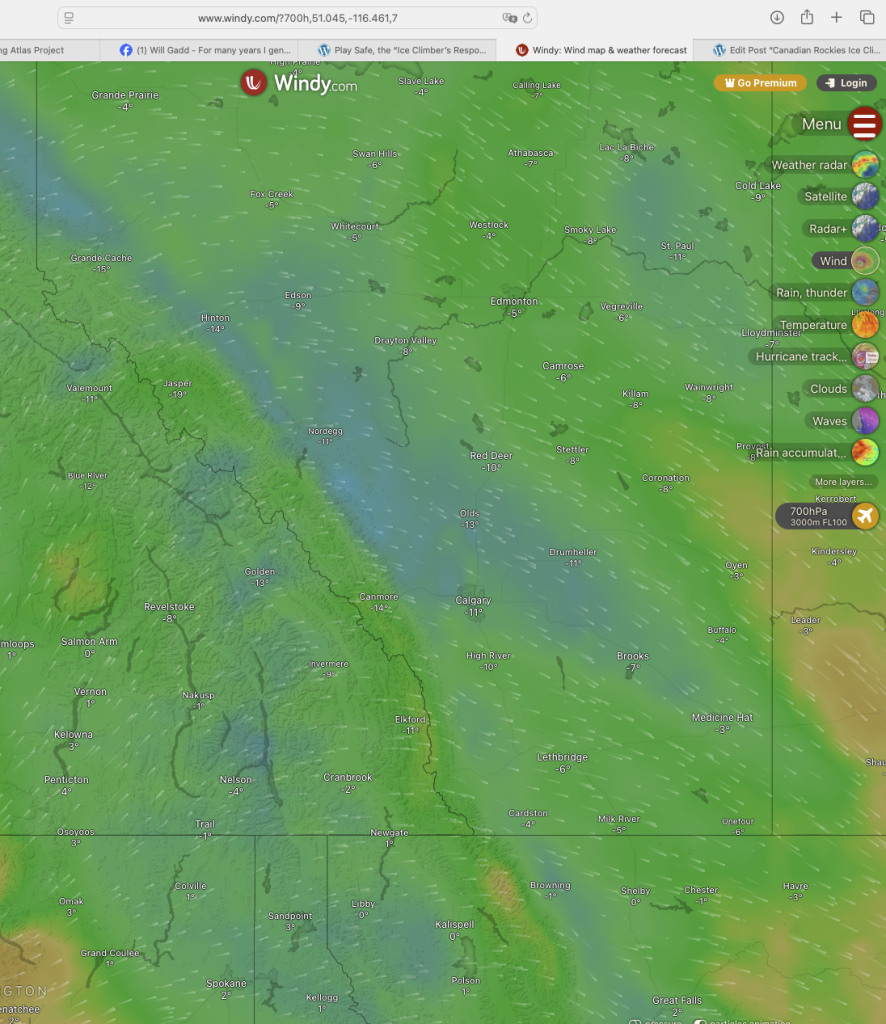

Step 5: Wind and temps

Wind and temperature matter here. Many if not most of our climbing avalanche fatalities here come from above, often as the result of wind transported snow building up in a slab until it overloads the snowpack under it, snow slides, ice climber (s) caught in a terrain trap and die. So, wind matters, a lot. I usually look on Windy.com, zoom into the Canmore-Jasper area or so and see what the surface winds are for the next 24 hours, then go to 6400ft with the altitude slider, do the same, and 10K, do the same. I use feet because aviation globally is in feet, but simple enough to convert, it’s the same info regardless of units at each step.

6400ft + is often about treeline, 10K is about ridge to summit height. Snow transport starts at about 20K, so if there’s any fresh snow left on the windward side of features it’s likely going to move when the forecast is calling for 20+. It starts really moving about 40K. If there’s more than about 30K and enough snowpack to slide then I’m stepping back from ice climbs in avalanche terrain. You’ll probably get away with pushing that, so it’s a question of how long you plan to climb in in your life. Me, I’m five decades in and don’t feel like I have a lot of “probablies” left… If you’re considering the Ghost those surface winds are VERY important, I’ve been stuck in there a few times when the winds picked up and turned 10cm of fluff into truck eating drifts in the late afternoon.

Switch the primary view to temperature and the shades will give you a pretty good idea of how cold or warm it is. Run the slider from now until the end of the day you’re thinking of climbing on; a high of +6 isn’t a big deal if the temps are below freezing for all but a few hours of the day, but rockfall or solar load could be an issue. It’s often up to a 15C swing between the east and west side of the Rockies, or Jasper to south of Canmore. -25 can be tolerable in the sun in February for a few hours, but climbing at temps below -20 is something I don’t do a lot of, freezing your feet just sucks, and happens a lot more than expected. We all run heated socks up here in winter because we’ve frozen our feet.

Switch the primary view to temperature and the shades will give you a pretty good idea of how cold or warm it is. Run the slider from now until the end of the day you’re thinking of climbing on; a high of +6 isn’t a big deal if the temps are below freezing for all but a few hours of the day, but rockfall or solar load could be an issue. It’s often up to a 15C swing between the east and west side of the Rockies, or Jasper to south of Canmore. -25 can be tolerable in the sun in February for a few hours, but climbing at temps below -20 is something I don’t do a lot of, freezing your feet just sucks, and happens a lot more than expected. We all run heated socks up here in winter because we’ve frozen our feet.

ROT 4: If the predicted ridge top winds are over 40K I’m staying out of avalanche terrain in the main ranges. Ghost still likely OK to climb, it’s always windy there, so the snow gets sandblasted into very hard slabs or blown east somewhere. But not always OK in the Ghost, I’ve seen size 3 debris at the base of many of the bigger routes.

ROT 4.5: Just go cragging in the sun when the highs are below -10. Trust me.

Step 5: Now, where to climb?

OK, so now you have general idea of what’s going on: What the snowpack generally is (decent, scary, horrible aren’t colours on the chart but that’s kinda how I look at it) in different areas, what the weather coming in looks like, wind, temps and what routes/aspects/elevations are likely good climbing. Now I start to get more specific based on routes that looked good, lines I want to do, haven’t done, etc. Then it’s back to the same sources but for more specific information:

-Back to Avalanche.ca to look at specific climbs on the Ice Atlas. This shows the climb’s avalanche path, some ideas on frequency, ATES rating, and is just really useful info for a lot of the more common climbs in the Rockies. I refer to this regularly, it’s just a great resource developed by Grant Statham, Sarah Hueniken and hundreds of climber survey responses.

– I pull a SpotWX point (this one for the Stanley Headwall Climbs roughly) for the climbs in the top three or so. What are the predicted winds, temps, etc? Predited precipitation amounts are also here. If there is more than 10cms fresh forecast I’m probably going to low ATES climbs. Wind and more than 5cms I’m going to low ATES climbs.

I pull a SpotWX point (this one for the Stanley Headwall Climbs roughly) for the climbs in the top three or so. What are the predicted winds, temps, etc? Predited precipitation amounts are also here. If there is more than 10cms fresh forecast I’m probably going to low ATES climbs. Wind and more than 5cms I’m going to low ATES climbs.

–Road conditions. If I’m pondering going up the Parkfields Iceway (what the locals call the Icefields Parkway for good reason) then it’s good to know if it’s closed (it often is), in decent condition, etc. There’s also a useful Facebook group for Canmore area conditions, and Banff-Jasper conditions. These matter. Also the 4wd groups for the Ghost.

Now I can make real plans! If the overall hazard is higher than “moderate” then let’s say I want to climb about WI4 in ATES 1-2 terrain. Check the Ice Atlas, App, social, etc: Say Evan Thomas, Weeping Wall look good. But the road conditions on the Parkway are hideous, better go east so Evan Thomas? But it’s brutally cold on the Rockies side of the divide (I don’t climb multi-pitch routes with high temp of less than -10 or so, just not worth it anymore), so maybe the Columbia Valley side where it’s usually warmer, about 5C warmer or more over there. Gibraltar Wall looks cool, saw a Social report it was in, plus Cascade is and that’s roughly the same for too aspect, short approach, in the sun, low avi hazard, boom! But I better have a plan B and C too, so maybe Green Monster if the roads are bad, Haffner if all else fails. Haffner is always where we end up when everything else fails :).

ROT 5: Only go for the “big rigs” when the hazard is “Low.” Most of the “classic” big routes are below big avalanche terrain, or require being in it to reach. Ghost routes are generally lower hazard so you can do Hydrophobia or the Sorcerer with more hazard, but they both have cornices, and I have seen size 2 debris in each area. Hydro in particular has a slope above it on the right that gets wind loaded and pulls out even on sunny days.

If you don’t know the aspect, ATES, etc. of routes in the Canadian Rockies then here’s a plug for Ice and Mixed Climbing, an App Steven Rockarts and I did. It has every known route in the Rockies, with as much information as we can provide on the location, approach, etc. etc. Buy it once, and you can sort by aspect, ATES, WI difficult, etc. etc. I use my own App a lot for the final planning stages of a day out. Very useful, I basically made it to help us figure out climbs in the Rockies. Also has good areas for toproping,

A few other resources:

Parks Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale.

Why Falling off on ice sucks

Ice Atlas: Critical Information.

Posted in: Blog

Date: November 11th, 2025

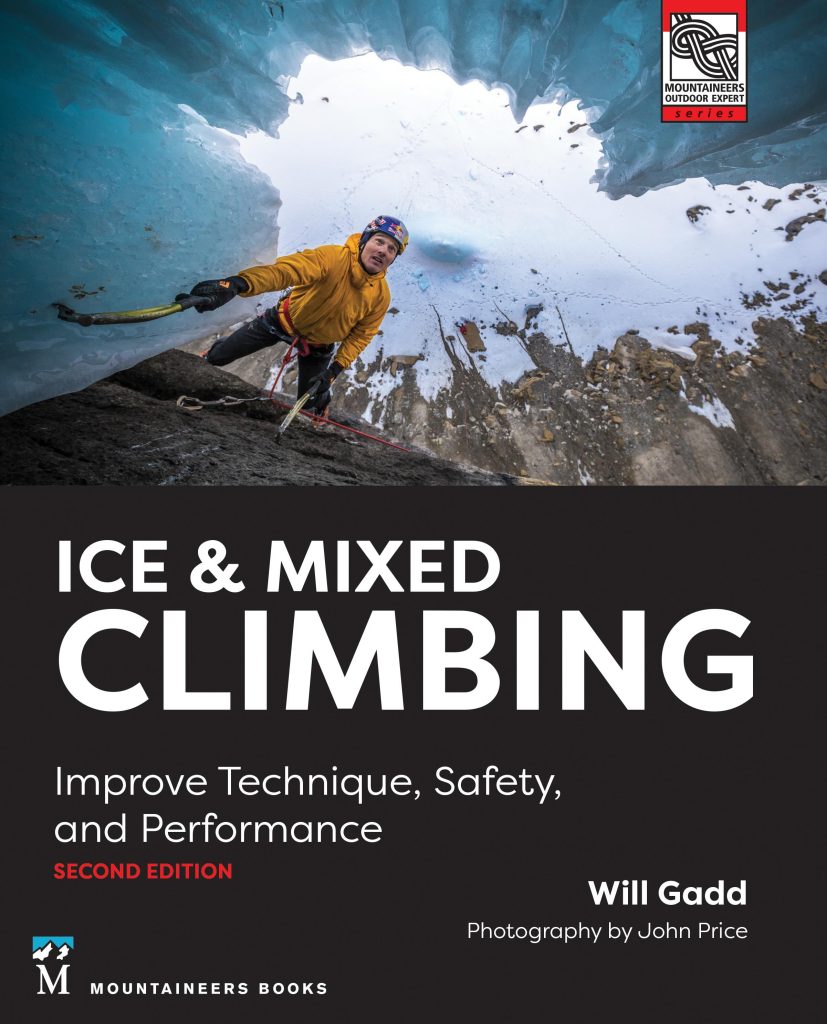

Only two years late, but I hope the result is worth it! Great John Price photographs, and everything I’ve learned and unlearned in the last 40-plus years of swinging, hooking, stein pulling and otherwise using and abusing ice tools globally! My hope is that this book is as useful to people as the first edition seemed to be. A lot has changed in the last 20 years, and this book is a brain dump of tactics, safety, movement, nutrition, training, and anything else that will help people enjoy climbing steep frozen water. Drills to improve efficient movement, how to understand what is a solid placement and what isn’t, why how frozen the ground is matters a lot more than current temperature for ice safety, new belay tactics, how not to get killed in an avalanche, and an encyclopedia of everything else I’ve learned as a climber, competitor, guide–and while making tons of mistakes you don’t have to make.

If you have questions please hit me up! Available at your local outdoor and book shops, which are my first choice for buying anything, to Amazon in the USA and Canada, to the Mountaineers, to Indigo, well, everywhere! A huge thanks to the Mountaineers for their immense patience and editing, John Price for his great imagery and fellowship in the suffering, and to everyone who helped teach me how to do this wonderful, crazy sport of ice climbing!

I’ll also be at the Ouray Ice Festival, Cody Festival, and Scarpa Ice Days in Italy if you’d like to meet up for a coffee, question or signed copy!

Posted in: Blog

Date: February 4th, 2025

“You know, sometimes I sit at home, you know, and I watch TV

And I wonder what would be like to live in some place like

You know, The Cosby Show, Ozzie and Harriet

You know, where Cops come and got your cat outta the tree

All your friends died at old age

But you see.. I live in South Central, Los Angeles

And unfortunately… SHIT AIN’T LIKE THAT!!

It’s real fucked up!”

-Ice T, not talking about the mountains but it resonates…

The below article first appeared in Explore Magazine in 2024. Recent events in the climbing world made me want to share it publicly again. For me, hazard should be a spice, not the main meal in life and mountain sport. But today I’m reading more celebration of climbs where the only thing that made them special was the hazard taken, and I think that, generally, confusing hazard as accomplishment or commitment is the same as celebrating hanging one-handed from a crane without a rope or playing Russian Roulette. Neither “accomplishment” requires a great deal of co mpetence, and I respect earned competence, not taking extreme risk and pretending it’s either competence or an accomplishment. To confuse the situation further, I do think we need to take real risks, but soloing El Cap after a tremendous amount of work and thought is not the same as most of what I see in the mountains today. The current body count reflects this…

mpetence, and I respect earned competence, not taking extreme risk and pretending it’s either competence or an accomplishment. To confuse the situation further, I do think we need to take real risks, but soloing El Cap after a tremendous amount of work and thought is not the same as most of what I see in the mountains today. The current body count reflects this…

This piece wasn’t written about any one specific event, but a bigger problem in our mountain sports world. The photo is of my dad, who survived 50+ years of climbing. That’s the goal, not just taking hazard to take hazard.

Scrambling to Death

“It’s a hike on Alltrails, I downloaded it, we’re good.” The youngish man telling me this was absolutely confident that he and his party of older (I’m older, and they were significantly older still) “hikers” were on an established trail with some “scrambling well within our abilities.” I knew because he’d just told me after I asked if he knew there was technical climbing terrain above him. I’d just come down the same “trail,” where we’d done two roped rappels down steep cliffs I would not comfortably climb up without a rope and some gear. I tried to politely engage as I do often in the mountains while guiding or climbing on my own: “So, ah, I just came down this ridge, and it has some real rock climbing above us. Have you been up here before?” But Mr. Confidence was not deterred, and promptly showed his non-impressive climbing abilities by latching onto the steepest piece of rock in the immediate area, indiscriminately yanking on holds like he was in the climbing gym with a thick matt directly under his feet instead of 50 feet of air. But this is the Rockies, and holds break as often as they stay put. His, and I use “his” as he seemed to be the nominal leader in volume if not experience, group started looking for an easier way up.

After decades of climbing and guiding I now can’t watch anyone climb without automatically assessing their base movement skills and understanding of the rock. This judgement really matters when I’m about to tie into a rope with someone who may kill me if they fall off, so I have an intense interest in how people move in high-consequence terrain. A few moves told me that Mr. Confidence had climbed very little on real rock, and his crew less. The climbing above was not going to be easy or smooth for them. I tried once more to engage, but Mr. C overrode my mild questions with a loud voice directed toward his crew. OK then, I shrugged internally, and continued scrambling down with my partner. But the situation really bothered me: I’ve picked up after a lot of serious mountain wrecks, and I just didn’t like what I saw coming. I’d tried and failed to engage, but I didn’t want to have to respond to screams shortly, or see the bad news and wish I’d done more.

The last few years and months in particular have been especially lethal for “soloists” and “scramblers,” words that need definition because they can mean a lot of things to different people. Traditionally, “scrambling” means moving through steep but non-technical terrain where a fall will usually result in “bumps and bruises” to maybe “hospital” on the scale my kids (and guests) and I use to assess any hazard in the mountains. A scramble might have a very easy “death” move or two, but “scrambling” terrain isn’t where most experienced or even novice climbers would use a rope. “Soloing” means doing climbing moves without a rope that would normally be done by guides or climbers with a rope. There are a thousand shades of grey in this, but generally “scrambling terrain” is primarily a consequence, not difficulty, rating for relatively steep and relatively easy mountain terrain punctuated with enough ledges to stop someone who slips. Most “scrambles” still have a lot more “Hospital” terrain than a mere hike, but the people above me were not on what the popular and often genuinely useful but also often wrong Alltrails App described in the title as a, “Pleasant but strenuous hike.” I’ve changed the words a little to keep this anon, but close enough. Oddly the “AI generated summary” read, “This is not really a hike, more of an alpine rock climb, and you should bring a rope and gear and know how to use it.” These AI summaries are relatively recent, and reflect the user comments, not just the person who submitted the “trail” to the App.

The user reviews of the “trail” ranged from, “Easy scramble, don’t know what the big deal is” by a user with the username, “I.am.cooler.than.you,” to, “We almost died, this is NOT a trail, WTF Alltrails?” to, “Scrambling level is 5.4-5.6 … stay calm , be patient, one wrong move and you are dead.“ That last comment is close to verbatim and close to insane. It’s NOT a scramble by difficulty or consequences. But apparently Mr. C had focused on what he wanted to see, and was now intent on showing off his “scrambling skills” to the group he was with. He had veered from a “trail” right through a “scramble” and was now charging hard on “solo” terrain, while still proclaiming they were all on a hike.

But it’s not just erroneous “trail” descriptions on Alltrails. We climbers (ropes and clinky bits, falling doesn’t equal death generally) have taken to social media with photos and captions of ourselves “scrambling” technical climbing routes such as the NE ridge of Ha Ling, 450M 5.6 (those are absolutely climbing, not scrambling grades, and you will die if you fall without a rope). It’s become common to fashionable among the elite and not so elite climbers to refer to soloing relatively easy but still absolutely technical multipitch routes where a slip will result in death as mere “scrambles.” The term diminishes the real hazard and consequences of normal human error. People make mistakes, and in scrambling terrain that generally shouldn’t kill them. In the risk management world we’d call this “normalization of deviance,” meaning it becomes culturally OK to do high-hazard or “stupid” shit because it’s “normal.” Generaly this collective slippage is obvious in retrospect, but seems “normal” at the time. The number of deaths and bad accidents this year in particular and in the previous five years cumulatively is way beyond “normal.”

Solid statistics on scrambling/soloing deaths are hard to come by (and the quote, “There are lies, damn lies, and statistics” is 100 percent accurate,) but the endless stories of yet another young man (young men are special) dying without a rope on are way too frequent to ignore. The well-respected if academically reserved editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, Pete Takeda, wrote in the most recent issue, “Free solo deaths are becoming alarmingly frequent.” I try not to confuse reality with social media, but a recent post noted that there were more solo/scramble deaths in the US than in the last three years than the previous 10 or so put together. I dug into the author’s methodology and roughly corroborated it through another source. I also believe Takeda’s view is accurate, although it could use a few less-reserved expletives in front of “alarming.” Something is going on: a LOT of people are dying soloing/scrambling.

Alex Honnold, the guy who free-soloed Yosemite’s El Capitan and starred in the hugely popular “Free Solo” documentary film, has also often used “scramble” for soloing a lot of easy (technical with fatal falling consequences but easy for him) terrain. The El Cap solo film has often been blamed for popularizing solo climbing. A few years after “Free Solo” came out another excellent film profiled the late and larger than life Canadian climber and soloist, Marc Andre Leclerc. And there are innumerable social media reels celebrating ropless soloing. These are similar to the “influencers” hanging one-handed from cranes or leaping between buildings; they die too. The social media for the climbing publications regularly celebrates the most recent “Super rad solo of mega alpine route!” with a beautiful picture and story of the protagonist’s daring feat. But the deaths usually get only a brief black and white mention for a GoFundMe page. If “normalization” of high-risk deviance leads to poor outcomes then what does full-throated celebration lead to? Maybe guys like Mr. C confusing their abilities with Honnold’s?

I was once a guest on Honnold’s podcast and remain a listener because I respect his take on risk and reward, and agree that people are, and should be, free to make their own decisions. Alex has thought a lot about the extreme risks he takes, and is a genuine, caring person. But I think he, and other social media/cultural leaders, may be under-estimating the effect their words and images have on people like Mr. C., or the many other “scramblers” who died lately. I don’t think we can directly blame the films or social media wanna-be solo stars any more than we can blame the fallen; it’s now a cultural problem, and needs a cultural solution.

If people are truly at peace and honest about the risks and rewards of any outing then I have no issue with that. But it’s hard to reach that state of calm reason about insanely fun activities, and soloing/scrambling is absolutely exhilarating if you’re in the mindset for it. Some interesting research covered in, The feeling of risk, by Paul Slovic, makes the point that, “When we desire a benefit/reward then we see the risks as lower than they actually are.” Behind that dry language is a hard truth about risk: Climbing mountains without a rope feels marvelous, until it doesn’t. And social media doesn’t show the SAR teams recovering the broken bodies. And I think that the positive hype for high-consequence behaviour without also showing the real downside of the same, combined with the deliberate minimization the risks, has caused much of the surge in accidents and deaths that concerns Takeda and that many SAR groups are also reporting.

The above and the multiple recent horrible “scrambling” deaths in BC and Alberta went through my head as I started down the ridge, and so I turned and scrambled back up toward the group of fellow oldsters. “Um, sorry to bother you again, but I live here and do this a lot, and I’m concerned about that big storm cloud up the valley. Has anyone looked at the weather radar lately?” I had, and that cloud was turning into a savage, feral example of the aptly Latin-named, “Cumulusgonnafaqus” by the minute. But Mr. C was still confident: “Yes, the forecast last night was rain by 2, and it’s only 1. We’ve got time, don’t worry.” There was still at least 200M of steep to vertical terrain above them, and given what they’d managed to get up by 1:00, the summit, and descent, weren’t looking likely in a dry state, never mind with some lightning for bonus atmospherics. Wet rock complicates climbing fast, and lightning always adds effective but non-helpful urgency. “OK, the weather radar is showing that storm hitting here in about 30 minutes potentially.” I could see the gears turning under the grey hair and large packs of the older members, and upward progress stopped. Mr. C wasn’t phased though, “Well, radar, forecast, whatever I’m sure it’ll hold off, we just need to keep moving.” This comment was finally met with some discussion by the group, one of whom said, “Ah, that’s a really black cloud headed our way, maybe we should get back down into the big trees?” “No, we’re fine!” More discussion ensued, but I felt I’d done what I could, and faded back down.

The mountains aren’t safe, and neither Alex nor I nor the social media posters are responsible for any one outcome. But, from Alltrails to Alex to me and you, we make our own culture, and I feel we’ve gone seriously off-route with our risk assessment and portrayal of scrambling and soloing. The very classic and very wrong comment that, “The drive is the most dangerous part of the day!” is on the same continuum of calling technical rock solos “scrambles.” We really do often minimize the real risks when the outcomes are desirable. I just hope my culture, from the old to the young, can get a little more realistic in our mountain risk taking, and stop normalizing the wildly abnormal. Risk is essential to growth and meaning in life, but so is being honest with ourselves about those risks.

PS, I have no idea what happened to that group, but I didn’t read about them that night, and don’t think I will in Accidents In North American Climbing. Maybe they’re calling me the “roving pessimist jerk”, but I’m OK with that compared to doing CPR.

Posted in: Blog

Date: November 14th, 2021

2017 version below.

Welcome to the Canadian Rockies, home of an epically long ice season, epic amounts of ice climbing, expensive beer and stoked people! I often get asked for information about climbing here, so I’ve written a few documents that I hope will help both new and visiting climbers have a good trip. For a general understanding of our season and ranges, check out this link. We reliably have ice from mid-October to early May or later. If you’ve read the “ice season” link then you kind of know the basics of what forms first and melts last, etc. There’s also a page on “Canmore Resources” with places to stay, eat, drink, etc. I’m not paid on any of those recommendations. Big Picture: When I go to a new rock climbing area I often have a list of routes I want to do, and then adapt that a little based on the weather and crowds etc for each day. Winter climbing in the Canadian Rockies doesn’t work that way. The Rockies tell us what we can and can’t do, and then we figure out how to fit our climbing into current avalanche and ice conditions. Many visiting/new climbers show up here with a list of dream routes without looking at the current conditions, and some don’t survive. The following is my workflow for deciding what to climb whether it’s a personal mission or getting my guests the best possible day. I look at this info every night starting in mid- October, and often in the morning before going. I’m doing a video of all the info below, but wanted to put it in text form so people can reference it easily etc. Fast Overview, Detail below: 1. Start on avalanche.ca for avalanche danger forecasts. That hazard level and the terrain determines where to climb, not what I want to climb. Also look at it for winds, the Ice Atlas, new snow, general mountain forecast, MIN reports, etc. etc, it’s just great. 2. Look at the public weather forecasts for Canmore, Lake Louise, Jasper, and maybe Radium. 3. Look at social media, see below. With the MIN this should give a pretty good idea of what’s going on. 4. Research. Use the Ice and Mixed App for location info etc. Short list a few climbs. 5. Pull a Spot WX specific forecast for your potential climb. If you don’t use this already learn it, it’s great. 6. Check road conditions, links below. 7. If climbing in terrain that can slide bring avalanche gear at least to the base. 8. Bring satellite coms. Some phones work some of the time sometimes. Bring a dedicated sat com device. 9. Ice Climber’s code. Yes. 10. Send and Survive.

Rule of Thumb (ROT) 1: For ice climbers, add at least one “level” to the danger rating scale. The CMOH (conceptual model of avalanche hazard) that drives the ratings is built around the size and probability of slides, and the consequences of the same–and much of the data and perspective in the CMOH is based on skiers and cars, not ice climbers, and on the “good” snowpacks skiers tend to seek, not the north-facing facet farms/thin snowpacks most ice climbs are in. A size 1 is by definition survivable for a skier and will result in a lower hazard rating, but for ice climbers even a small 1 is very much enough to ruin our day by knocking us off on lead or sending us over a cliff edge if walking between steps. A size two that would be relatively easily avoided by a skier on a planar slope is very different than a size 2 filling up a ten-foot wide ice gully 15 feet deep…. Most ice climbs are in nightmare terrain traps, and climbers have been killed in slides that wouldn’t likely ruffle a skier’s feathers much. We’re often also in gully features below big, multi-aspect terrain, so, unlike skiers, anything that slides on any aspect above us will end up on us. And we’re there for hours, tied in place. And we can’t adapt fast to changing conditions by pointing the skis downhill and getting out in minutes, or changing aspect. So, I add a level to the danger rating, and have found that to be a more accurate representation of the hazard.

Rule of Thumb (ROT) 2: If the “Danger Rating” is above “moderate” at any altitude I’m in or exposed to I’m generally just avoiding avalanche terrain greater than 2 (challenging) on the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES). There are enough routes to climb that are a 1 or 2 on the ATES scale (List of climbs in Simple etc. terrain here, excellent)) in the Canadian Rockies that you an almost always go climbing. Even with “moderate low low” climbers have died here. If you’ve spent a lot of time in the snowpack and terrain here then you will probably be able to make your own more nuanced judgements, but to me “Mod Low Low” means “Considerable” in the Alpine, Mod at treeline, and Mod below treeline. I’ve been there when the day goes bad, and you do not want that experience.

There’s a list of “simple” routes in the Ice and Mixed App, as well as on the Parks Canada page. This page is excellent information in its own right for anyone coming climbing here. . The list for Kananaskis Country is currently unavailable.  If you start with avalanche danger then route selection is much simpler, and safer. At the beginning of every season I start reading the avalanche bulletinss on avalanche.ca. I read them every single day for Kananaskis, Banff Park, Little Yoho (Field), and Jasper National Parks. If you read them as the season develops you’ll also develop a sense of what the problems are, and how the local professional forecasters look at the snowpack.

If you start with avalanche danger then route selection is much simpler, and safer. At the beginning of every season I start reading the avalanche bulletinss on avalanche.ca. I read them every single day for Kananaskis, Banff Park, Little Yoho (Field), and Jasper National Parks. If you read them as the season develops you’ll also develop a sense of what the problems are, and how the local professional forecasters look at the snowpack.  But there is a lot more information on Avalanche.ca. In the upper left corner there’s a drop-down menu bar with three other critical pieces of information: The Mountain Information Network (MIN), real-time weather stations and a “mountain forecast.” The MIN is an collection of user-generated reports, and you can sub-sort them by type. I look at both the ski and ice climbing reports (how cool is it to have that feature!), and if you look on the map each report has a blue label around it. Often there are reports for the more popular areas, but I look at all of them. If skiers are reporting afternoon class 2 slides on features below treeline then that is excellent information! The Av Can weather stations are an often-overlooked resource. See the screenshot, but each little mini weather station logo has a variety of information. For Field I check the Bosworth stations, for the Parkway the Parker’s Ridge Station, etc. These are vital because they tell you how much it has snowed recently, and how windy it has been, trends, etc. If it’s snowed more than a few centimetres or it’s windy above about 20 kmh then there are likely to be wind slabs growing, bad. The forecasts may lag this information by a lot–the stations are real time. As noted in the Guide’s report on the Masseys fatal avalanche two years ago, these stations can be useful for monitoring winds/snow in real time. High winds and snow are just a bad combination in the Rockies, especially if you’re an ice climber under slabs that are forming rapidly over your head. If you’re low in the valley it can be really hard to see what’s happening at the ridge top level. Somewhere around half the alpine/ice climbing accidents are natural slides from above, not triggered by the climbers, so you’ve got to think defensively at all times. The Ice and Mixed App has the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale for 99 percent of the climbs in the Canadian Rockies, as well as suggestions on where to go in higher avalanche conditions. Let’s say the hazard is “Considerable” in most areas at all elevations, and there’s a storm coming in. I’m going to be thinking about climbing in Simple terrain at most, and what roads are going to close so I can get home in the evening, and will definitely NOT be out in bigger terrain. Even if the forecast is “Low” everywhere you’re still using your judgement, “Low” does not mean give ‘er here. But Low/Moderate is a, “Yeah, I’ll research bigger terrain, what types of hazards, terrain.” “Considerable” and above has me on the low hazard, low exposure routes. “High” generally means Haffner or other “never seen a slide there” terrain, or maybe going skiing at the hill, it’ll be good! If you do the above then you’ll have a handle on the biggest hazard ice climbers face, and can choose your terrain appropriately. Often the forecast for the Parkway is quite different than for Kananaskis, don’t be afraid to drive, we do a lot of that here. If I have doubts then I start scaling it back. Note that if you have specific questions or concerns you can call Banff Park Dispatch or Jasper or K-Country and ask to speak to a “Visitor Safety Specialist.” Don’t do this if you’re going to a very common route with low avalanche hazard, but if you have concerns about a bigger route or something obscure, then don’t be afraid to call them up. Please be organized and succinct with your question as they are busy, but they like talking snow and hazard, good people we’re lucky to have. Also check the “General South BC forecast.” Very useful. And the “Backcountry Resources,” more great info! Public Weather Forecasts: How cold is it going to be, any big storms forecast, sun? If it’s below about -15, maybe -17, I don’t go multi pitch climbing. It’s miserable, and if there is an accident the temps could turn a broken ankle into a fatality. Go run laps in a single pitch area, stay warm, have fun. If it’s March and sunny then sun–effected slopes are going to be an issue. In January it’s probably where you’ll want to be on a cold day. It’s often warmer just over the continental divide (Haffner, Field, Radium, Golden) than it is to the east of the divide, check out the public forecasts. Research, Social Media I then hit social media for reports on what has been climbed and not. Facebook is about the best place for this right now, and there are two groups: Rockies Ice and Mixed Conditions is straight up conditions reports, usually pretty solid. Canadian Rockies Ice Climbing is more random, and you may get some insight into local drama, but there’s a good thread on Ghost Road Conditions (very relevant) and often some decent info. Scroll back through both, there’s a wealth of information there. One resource that’s often overlooked is the ACMG Mountain Conditions Report. These are reports submitted by guides, so generally solid. A lot of ski conditions, but also ice info. The “Regional Summary” is also very useful, I check it all year for alpine climbing etc. Research Access, Descent, etc. There unfortunately isn’t a good guidebook to the Rockies in print. But there is an App, which has every route in the Joe Josephon’s out of print Waterfall Ice guidebook, all the routes from Sean Isaac’s Mixed Guidebook, and 99.99 percent of all the new routes done since then. It also has GPS parking and route locations for about 750 of the 1500 routes in the book, and GPS traces for several hundred. It will save you a LOT of time. Please consider sending in a trace if you do a route that doesn’t have one, thanks! It’s continually updated. Mountain project also has good info, and of course search the internet, a LOT out there. If you’re looking for a paper guide Brent Peter’s nice “Ice Lines” has some classics. Terrain Angle in Mapping Apps/tools. Many now have shading for slope angle, which can tell you a lot about the snow collection area and slide potential above a route. CalTopo is currently my favourite, but also available in FatMap etc. I like to do a route plan, with rough times on it, descent notes, (number of raps, station location), times for various points, alternatives in the area in case people are on “my” route, etc. This just helps me stay organized, and think ahead. Grades are really arbitrary, but the big idea is to climb something you’ll enjoy, and not whip from. I’ve written lots on why falling on ice sucks, enough already, but try to choose something that seems like you can enjoy it. Or go toproping and enjoy that, yeah! I generally try to under-call the day a little bit so I have a margin in case something goes wrong. It’s much more fun to be back in the bar saying, “Yeah, we sent that, could have done another one!” than, “Shit, it’s dark, let’s snuggle while we wait for light…” I could write a book on all the rest of the pre-trip planning stuff, but this is getting long already so let’s keep moving… Pull specific Spot WX forecast

But there is a lot more information on Avalanche.ca. In the upper left corner there’s a drop-down menu bar with three other critical pieces of information: The Mountain Information Network (MIN), real-time weather stations and a “mountain forecast.” The MIN is an collection of user-generated reports, and you can sub-sort them by type. I look at both the ski and ice climbing reports (how cool is it to have that feature!), and if you look on the map each report has a blue label around it. Often there are reports for the more popular areas, but I look at all of them. If skiers are reporting afternoon class 2 slides on features below treeline then that is excellent information! The Av Can weather stations are an often-overlooked resource. See the screenshot, but each little mini weather station logo has a variety of information. For Field I check the Bosworth stations, for the Parkway the Parker’s Ridge Station, etc. These are vital because they tell you how much it has snowed recently, and how windy it has been, trends, etc. If it’s snowed more than a few centimetres or it’s windy above about 20 kmh then there are likely to be wind slabs growing, bad. The forecasts may lag this information by a lot–the stations are real time. As noted in the Guide’s report on the Masseys fatal avalanche two years ago, these stations can be useful for monitoring winds/snow in real time. High winds and snow are just a bad combination in the Rockies, especially if you’re an ice climber under slabs that are forming rapidly over your head. If you’re low in the valley it can be really hard to see what’s happening at the ridge top level. Somewhere around half the alpine/ice climbing accidents are natural slides from above, not triggered by the climbers, so you’ve got to think defensively at all times. The Ice and Mixed App has the Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale for 99 percent of the climbs in the Canadian Rockies, as well as suggestions on where to go in higher avalanche conditions. Let’s say the hazard is “Considerable” in most areas at all elevations, and there’s a storm coming in. I’m going to be thinking about climbing in Simple terrain at most, and what roads are going to close so I can get home in the evening, and will definitely NOT be out in bigger terrain. Even if the forecast is “Low” everywhere you’re still using your judgement, “Low” does not mean give ‘er here. But Low/Moderate is a, “Yeah, I’ll research bigger terrain, what types of hazards, terrain.” “Considerable” and above has me on the low hazard, low exposure routes. “High” generally means Haffner or other “never seen a slide there” terrain, or maybe going skiing at the hill, it’ll be good! If you do the above then you’ll have a handle on the biggest hazard ice climbers face, and can choose your terrain appropriately. Often the forecast for the Parkway is quite different than for Kananaskis, don’t be afraid to drive, we do a lot of that here. If I have doubts then I start scaling it back. Note that if you have specific questions or concerns you can call Banff Park Dispatch or Jasper or K-Country and ask to speak to a “Visitor Safety Specialist.” Don’t do this if you’re going to a very common route with low avalanche hazard, but if you have concerns about a bigger route or something obscure, then don’t be afraid to call them up. Please be organized and succinct with your question as they are busy, but they like talking snow and hazard, good people we’re lucky to have. Also check the “General South BC forecast.” Very useful. And the “Backcountry Resources,” more great info! Public Weather Forecasts: How cold is it going to be, any big storms forecast, sun? If it’s below about -15, maybe -17, I don’t go multi pitch climbing. It’s miserable, and if there is an accident the temps could turn a broken ankle into a fatality. Go run laps in a single pitch area, stay warm, have fun. If it’s March and sunny then sun–effected slopes are going to be an issue. In January it’s probably where you’ll want to be on a cold day. It’s often warmer just over the continental divide (Haffner, Field, Radium, Golden) than it is to the east of the divide, check out the public forecasts. Research, Social Media I then hit social media for reports on what has been climbed and not. Facebook is about the best place for this right now, and there are two groups: Rockies Ice and Mixed Conditions is straight up conditions reports, usually pretty solid. Canadian Rockies Ice Climbing is more random, and you may get some insight into local drama, but there’s a good thread on Ghost Road Conditions (very relevant) and often some decent info. Scroll back through both, there’s a wealth of information there. One resource that’s often overlooked is the ACMG Mountain Conditions Report. These are reports submitted by guides, so generally solid. A lot of ski conditions, but also ice info. The “Regional Summary” is also very useful, I check it all year for alpine climbing etc. Research Access, Descent, etc. There unfortunately isn’t a good guidebook to the Rockies in print. But there is an App, which has every route in the Joe Josephon’s out of print Waterfall Ice guidebook, all the routes from Sean Isaac’s Mixed Guidebook, and 99.99 percent of all the new routes done since then. It also has GPS parking and route locations for about 750 of the 1500 routes in the book, and GPS traces for several hundred. It will save you a LOT of time. Please consider sending in a trace if you do a route that doesn’t have one, thanks! It’s continually updated. Mountain project also has good info, and of course search the internet, a LOT out there. If you’re looking for a paper guide Brent Peter’s nice “Ice Lines” has some classics. Terrain Angle in Mapping Apps/tools. Many now have shading for slope angle, which can tell you a lot about the snow collection area and slide potential above a route. CalTopo is currently my favourite, but also available in FatMap etc. I like to do a route plan, with rough times on it, descent notes, (number of raps, station location), times for various points, alternatives in the area in case people are on “my” route, etc. This just helps me stay organized, and think ahead. Grades are really arbitrary, but the big idea is to climb something you’ll enjoy, and not whip from. I’ve written lots on why falling on ice sucks, enough already, but try to choose something that seems like you can enjoy it. Or go toproping and enjoy that, yeah! I generally try to under-call the day a little bit so I have a margin in case something goes wrong. It’s much more fun to be back in the bar saying, “Yeah, we sent that, could have done another one!” than, “Shit, it’s dark, let’s snuggle while we wait for light…” I could write a book on all the rest of the pre-trip planning stuff, but this is getting long already so let’s keep moving… Pull specific Spot WX forecast This looks confusing, but spend a few minutes, it’s not as weird as it looks, and it has far more information than the public forecast. I like the GEM LAM forecast generally, but find one you like ha ha :). The precipitation line is VERY useful, same with wind direction, temp, just great. With the above you’ll have a decent idea of what’s going on, and can start scheming. If a route is posted on Social Media then it’s likely going to get mauled, so I more use it for thinking, “OK, X and Y are in, both north facing at 2000M so that’s a good zone to look in, Z and A are south facing and low, not in, avoid those” etc. I may also call friends, or post on social media if I’m trying to figure out what’s going on out there. The better information you have the better decisions you can make. Avalanche Gear: If there’s enough snow to slide I bring it in the car just in case, you never know where you’re going to end up. Even on climbs such as Whiteman’s (very narrow canyon with small-seeming side chutes coming in) I’ve seen slides big enough to bury someone. So I bring the gear at least in the car and usually to the base if not up the route, and this has become common practice here. Communications: Cell phones work in Field, most of the Bow Valley (if you can see the road), but not generally in K country, 93 South (Radium parkway), or 93 North (Icefields Parkway). If you break your leg in winter and can’t call for help your odds of dying are really high. Nights are long and cold here. Almost everyone here goes out the door with an InReach satellite coms device both for the SOS function, and to text the boyfriend/dad/whatever that you’re OK but running late so don’t scramble the rescue just yet. These are awesome tools, just get one. Radios used to be the standard before satellite coms, but unless you’re pre-programmed with the repeater frequencies they are near-useless. Just get and bring an InReach. Road Conditions: Alberta British Columbia And we mostly play by the “ice climber’s responsibility code” up here, good info. Leave a note on your car, don’t climb under other people, that sorta thing. Oh, and you can hire me :). . I’m also happy to recommend other guides if I’m busy, please hit me with an email.

This looks confusing, but spend a few minutes, it’s not as weird as it looks, and it has far more information than the public forecast. I like the GEM LAM forecast generally, but find one you like ha ha :). The precipitation line is VERY useful, same with wind direction, temp, just great. With the above you’ll have a decent idea of what’s going on, and can start scheming. If a route is posted on Social Media then it’s likely going to get mauled, so I more use it for thinking, “OK, X and Y are in, both north facing at 2000M so that’s a good zone to look in, Z and A are south facing and low, not in, avoid those” etc. I may also call friends, or post on social media if I’m trying to figure out what’s going on out there. The better information you have the better decisions you can make. Avalanche Gear: If there’s enough snow to slide I bring it in the car just in case, you never know where you’re going to end up. Even on climbs such as Whiteman’s (very narrow canyon with small-seeming side chutes coming in) I’ve seen slides big enough to bury someone. So I bring the gear at least in the car and usually to the base if not up the route, and this has become common practice here. Communications: Cell phones work in Field, most of the Bow Valley (if you can see the road), but not generally in K country, 93 South (Radium parkway), or 93 North (Icefields Parkway). If you break your leg in winter and can’t call for help your odds of dying are really high. Nights are long and cold here. Almost everyone here goes out the door with an InReach satellite coms device both for the SOS function, and to text the boyfriend/dad/whatever that you’re OK but running late so don’t scramble the rescue just yet. These are awesome tools, just get one. Radios used to be the standard before satellite coms, but unless you’re pre-programmed with the repeater frequencies they are near-useless. Just get and bring an InReach. Road Conditions: Alberta British Columbia And we mostly play by the “ice climber’s responsibility code” up here, good info. Leave a note on your car, don’t climb under other people, that sorta thing. Oh, and you can hire me :). . I’m also happy to recommend other guides if I’m busy, please hit me with an email.

Posted in: Blog

Date: October 23rd, 2021

Canadian Rockies Climbing Cycle: Ice, Alpine, Rock, repeat!

By Will Gadd, November 2021

I’m often asked, “So, what’s the best season to climb in the Rockies?” I wrote the following so I wouldn’t have to keep writing it for people.

Big Picture For Visitors: The Canadian Rockies are a relatively narrow (about 100K) band of peaks that run along the continental divide from the US border north for 1000K or so. Generally they are quite dry on the eastern side with a solid continental climate, and somewhat warmer and much snowier on the western side. Most of the “famous” ice, alpine, and rock climbing is found between the US border (Wateron/Glacier national parks) and Jasper, but there is a lot north of Jasper to be found! The highest peak is Mt. Robson at just shy of 13,000 feet/4000M, but most peaks are in the 9 to 11,000 foot/3 to 3500M range. Valley floors range from 1500M to 800M, so big peaks despite low elevations. Generally speaking, we are about one month “colder” than Colorado/European Alps/New England, so a Canadian October is like their November, and our March is like their February etc.

The Cycle

Mid-October to Mid-November: Stoke for the Ice Freaks, Melt/Freeze ice season, creeping despair for the Rock Freaks. Increasingly good ice, normally low avalanche hazard, normally not brutally cold.

Right around October 14th the ice season reliably starts in the Rockies on above-treeline North facing aspects. This isn’t due so much to dropping temperatures, but sun angle. In mid-October the days start to get a lot shorter, and the sun just stops rising high enough to hit most north-facing terrain. This means that all the sheltered above-treeline north-facing terrain (ATNF) starts to freeze, and once the ground is frozen ice starts forming on top of it. Often there is still plenty of moisture, either from springs that are still running, glacial ice or melt-freeze snow in the sun, so a lot of the thin “smear” ATNF routes come in surprisingly fast. If there’s too much water then the latent heat in it won’t allow it to freeze to the ground, so the larger flow routes don’t freeze until the temperature really drops.

You can still climb rock on the lower and south-facing sport and even alpine routes fairly reliably until about October 15th, but you’ll have to start later as overnight lows are often below freezing at the tree-line areas. Sport areas such as Acephale generally get too cold around Oct. 14th, but you can push it if you’re really stoked. For rock, Echo Canyon, Lake Louise, the Columbia valley cliffs, stuff that faces some version of south is excellent from about Oct 1 until it’s mostly done by Nov. 10 or so.

Multi-pitch rock season is pretty much over around Halloween with the exception of the occasional day on Yam or other south-facing protected crags. For me the Banff Film Festival, in the first week of November, kinda marks the end of rock season. If you’re really motivated you can still find the odd day, but there are way, way more good ice days than rock days. What exactly is in when will vary, but by November 10 there’s enough ice for good ice climbing and guiding regardless of the valley temperatures. Generally you’re looking for north-facing routes above 6,000 feet (1800M). The good thing is that avi hazard is normally low, but not non-existent: Take gear, and be aware that we have major slides here in early November. Many of the early-season ATNF Ghost routes come in, this is the time to get them before the smears sublimate into snice or just fall off by mid-December. Ghost driving is good (remember you can’t drive into the North Ghost until Dec 1). Kananaskis Country is also a good bet, routes such as R&D are normally in by October 15 for sure, but it can be really busy as everyone charges up there. Take the very early or very late shift, I find this tactic takes care of the worst of the crowds. The crowded conditions will seem OK to anyone from Colorado, but it’s not so normal around here. The routes in behind Fortress also come in early and are far less crowded as you have to, gasp, walk! Normally a few new longer alpine rambles get put in around this time of year, and if you’re motivated there is a LOT to do. The smear routes on the Stanley Headwall, storm Creek, ATNF routes in Protection Valley, etc are good to go.

If this were Colorado we’d have a dozen new routes every October for sure. Not generally in: Field, anything with a hint of southern exposure on the Parkway or elsewhere, most stuff below treeline

The classic “Big Rigs” normally don’t totally form up until at least mid-November, with a few exceptions such as the Sorcerer, Hydrophobia, The Terminator Wall, and Slipstream. I’ve climbed on the Terminator Wall as early as late October, but it’s pretty easy to see if there’s any ice up there, and how good that ice is if you have a pair of good binoculars. In fact, binoculars are pretty much essential this time of year… Slipstream is also normally “in” if you like high-hazard easy ice in a great position. Early winter can be a good time to go as the cornice at the top isn’t normally quite so massive as it is in the spring. But the glacier travel can be more involved due to less snow covering the gaping chasms…

The Ghost is often “in” a lot earlier than people think. Routes such as The Sliver, Burning/Drowning and anything between Hydro and Sorcerer often forms up in late October, these routes are surprisingly high and face north, it’s cold up there earlier than would seem logical while basking in the sun in Canmore.

The Stanley Headwall is likely forming up decently by mid-November. Nemesis is usually climbed for the first time around November 1st, sometimes earlier and sometimes later. The good thing about early season on the Stanley is that you can walk in. The bad thing is the same, skiing is a lot more fun. But little avi hazard.

Hafner, Cascade, anything “low” or “sunny” is NOT in.

The “Alpine” is coming on also. A lot of routes in the Canadian Rockies are best done when the rubble is frozen up, and there’s enough ice to get excellent gear. The avalanche hazard is generally low also, which means climbs can be attempted in gullies and across slopes. that would seem suicidal later in the year. Melt-freeze routes are at their fattest, normally they will start sublimating and getting thinner by about the middle of November.

Skis not normally needed anywhere.

Mid-November to Mid-December: Rock done, Ice getting GOOD, Alpine ice ON, shitty to poor skiing.

Now we’re starting to get lots of ice choices. Even the south-facing routes along the Icefields Parkway (Polar Circus, routes on Mt. Wilson) etc. are coming in. Normally Whiteman’s falls is in enough to climb, and is wildly popular until the road access closes December 1. The Stanley Headwall is in, and depending on the year the ski in is happening too. Avi hazard starts to become more of an issue, but temperatures aren’t normally brutal so we don’t have a horrendous facet layer (AKA “The shite ball-bearing crystal smack down by the dirt upon which everything slides and kills people). Daylight is an issue—bigger climbs are normally started or finished in the dark, and you’ll want good headlights.

For mixed/ice cragging, Haffner is in but the creek can be a pain in the ass, Bear Spirit is coming in, the Cineplex has a good-sized creek flowing down the front of it but is OK to climb at depending on where that creek is running. Don’t climb on the mixed routes unless the rock truly is frozen, you’ll just break lots of holds and annoy the locals.

Field is forming up nicely but is generally a bit “later” than equivalent routes on the east side of the Rockies, variable. Normally enough in Field by the second week of December to climb.

This is prime Ghost season; not too much snow, most routes formed, creek crossings can be a bit involved due to thin ice, it’s great!

New alpine big-rig and classic lines in K-Country are often done this time of year, the melt-freeze is as good as it’s going to get, approaches are still primarily dry or only a few inches of snow.

Skis needed for approaching bigger routes along the Parkway or the Stanley headwall, but not for anything else. The road to the Terminator/Golf course shuts, mountain bikes are the way to go. Walking up to the Terminator requires no skis anytime of year unless there’s just been a massive dump, in which ase you don’t want to be there!

Mid-December to early January : Great ice, Alpine done, skiing poor to OK.

Now the ice routes with lots of water coming down them are coming in or in. Cascade, Takkakaw, Weeping Wall, Louise Falls, GBU in the Ghost, etc, it’s cold enough that anything moving freezes up. This also means the days are short and can be brutally cold; the locals generally don’t go out climbing below about -15 Celsius, but guides and Americans will push it down to about -35–once. Probably two thirds of the days are good climbing days, but the cold comes in “sets” of three to seven brutal days followed by a week or so of decent weather. We don’t normally get huge storms in this period, but regular “dustings” that slowly add up to a significant snowpack. This means the avalanche forecast and being solid in your avi-hazard judgement is important.

Grotto is in too, as is everything in Hafner, good season for mixed cragging if it’s not too cold.

This time of year a headlamp isn’t just a “good idea,” it will get used, as will the mega belay parka and spare gloves.

Not much “alpine” climbing is getting done, but sometimes it all comes together, there have been some good alpine ascents done this time of year despite the short days.

There might be one or two days where it’s possible to rock climb at Bataan or White Buddha, but the only people trying to rock climb are serious chalk monkeys without the means to head to Mexico.

Mid-December offers one of the two “best” times to visit the Rockies for ice climbing.

Early January to early February: The Dark Season . Cold, dark, dry, cold.

Everything is in, but the days are short and often cold. People still go ice climbing lots. Nobody goes rock climbing unless there’s a rare chinook (foehn). The sun doesn’t make a whole hell of a lot of difference in general, it’s so far away and at such a low angle that it’s almost irrelevant except from about 11-2, and even then you’re not getting sunburned. Still, there are lots of good days to climb, and everyone is motivated after the debauch of the holiday season.

The avi hazard can be severe, with a lot of growing/persistent problems and large surface hoar if it does snow. Historicaly, enough snow has fallen to be dangerous, but generally not enough to really sort the snow pack out or give a good base. Wind slab, a meter of facets as the “snowpack,” all the fun stuff the Rockies has to offer in the way of snow pack problems are fully on display and just waiting for a human, wind, or new snow. Then again, at -30 it’s bomber and sometimes it’s all bomber, but that’s rare. Oddly, we’ve been having warmer winters and more snow the last ten years or so. This sometimes results in a much better snowpack than I’d “expect” in the Rockies. Generally, the farther west you go in the Rockies the more snow there is and the better the skiing.

Skis normally needed for anything more than a 20-minute walk from the road that doesn’t get done a LOT. Polar Circus, Hafner, Cineplex, Whiteman’s, Louise, etc. don’t need skis as there are so many people going in. Skis are seldom used anytime of year in the “front” ranges, meaning the Ghost, eastern K-Country. But if you’re at all close to the BC border/continental divide and looking at a longer approach then skis are definitely needed. Snowshoes aren’t used much here, they are really slow and annoying ’cause they don’t slide downhill for shit. That said, they can be useful occasionally.

Mid-February to Mid-March. The sun is coming back slowly! More snow, ice great, not much alpine, odd day of rock.

The last week of February or the first two weeks or so of March is the other “best” time to visit the Rockies for ice climbing. The days are getting longer, the temps reasonable and everything is in about as good conditions as it’s likely to get (except the smear routes, they were gone in December). Often the avi hazard works in “cycles,” where it’s bad after a storm but then cleans up nicely. I really like early March in the Rockies, it’s still definitely winter but the sun is strong enough to be noticed, just feels great after a long winter.

The skiing is generally very good with an HS of 10cm on the dry eastern front ranges of the Ghost to about 150 along the Smith Dorien road in Kananaskis to 200+ in the areas on or west of the continental divide.

Some alpine climbing getting done, but the snow makes it a PITA unless you like skiing to peaks.

Mid-March to mid-April: Ice great to fading low, snowpack stabilizing, skiing great. Still “winter,” but the sun is strong.